|

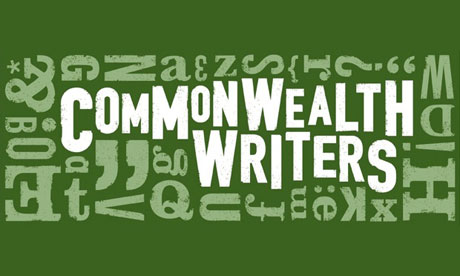

Today, the Commonwealth has 54 members and the Commonwealth

Foundation, a UK-based development organisation, works towards a world in which

every person on the planet is able to participate in, and contribute to, the

sustainable development of peaceful and equitable societies.

Commonwealth Writers is a cultural initiative from the

Commonwealth Foundation. Commonwealth Writers both develops the craft of

individual writers and also builds communities of emerging voices, so that,

individually and collectively, writers can work for social change, and

influence, directly and indirectly, the decision-making processes which affect

their lives. Commonwealth Writers wants the writers it

unearths to inspire others, especially in their local communities, and it challenges

selected authors to take part in on-line residencies, and

on-the-ground literary activities.

Commonwealth Writers runs the Commonwealth Short Story

Prize. This aims to identify talented emerging writers and to promote the best new

writing from across the Commonwealth, thus developing literary connections

worldwide.

The Short Story Prize is awarded for the best piece of

unpublished short fiction, of between 2000-5000 words. The language of the

competition is English. Writers can submit stories translated into English from

other languages.

Entries can be submitted from five regions: Africa, Asia,

Canada and Europe, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. The regional divisions are

intended to give writers in countries with poor publishing infrastructure a fairer

chance to compete with those in countries where there are more opportunities.

Within Asia, you are eligible to enter if you are a citizen of one of the

following countries: Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, India, Malaysia, Maldives,

Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka,

There will be five winners, one from each region. One

regional winner will be selected as the overall winner. The overall winner will

receive £5,000

(approx US$7,750)

and the remaining four regional winners £2,500 (approx US$3,785). Translators of

winning stories will also receive prize money. If the overall winner is a translation into English, the

translator will receive £2,000 (approx US$3,100).

Translators will receive £1,000 (approx US$1,150) for regional winners.

The 2014 judging panel will be chaired by Ellah Allfrey,

deputy chair of the council of the Caine Prize for African Writing, formerly

deputy editor of the UK-based literary magazine Granta and senior editor at Jonathan Cape, Random House, in

London. She will chair an international judging panel; this will make the final

selection. The regional judges will be announced on 1 October. Experienced

readers will assist the named judges in selecting the long lists.

The 2014 Short Story Prize will open for entry on-line on 1

October 2013 and close on 30 November 2013. Entry will be via www.commonwealthwriters.org

where you can view the eligibility criteria, and the entry rules.

So new Asian writers: Get writing! Tell the world what great stories, and what great storytellers, we have on this continent! If you need inspiration, click about on www.commonwealthwriters.org,

it’s a great website, with a mix of interesting tips and advice, discussion,

and constructively provocative comment.