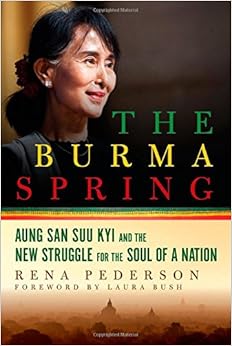

The Burma

Spring,

by award-winning journalist and former US

State Department speechwriter Rena Pederson, is a biography

of Aung San Suu Kyi. It offers a

portrait of the woman herself, and also portraits of Burma, and of the Burmese

people. (Burma was renamed Myanmar by the military government, but since this was not

democratically elected, Western policy has often been to refer to the country

as Burma. Rena adopts this policy too.)

Although

Rena doesn’t speak Burmese, she developed a network of sources inside and outside

Burma who could tutor her in the intricacies of the country’s politics, history,

and culture. When she began making

repeated trips, she came to rely on a trusted guide who often served as a

translator. Her local contacts and sources

helped enormously when she came to write The

Burma Spring.

So: over to Rena…

Why are you

so drawn to Burma?

A newspaper story in 1991 first inspired

me to learn more about Burma. It was about the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to

Aung San Suu Kyi for her efforts to bring democracy to Burma. At the time, she was being held under house

arrest in Rangoon, cut off from her husband in England and their two young

sons. I found it intriguing that she

played Bach and Chopin on the piano for hour after hour to stay occupied.

I went on to learn that Suu Kyi

was Oxford-educated, spoke four languages fluently and read Les Miserables in

French. She tutored her guards about Gandhi and meditated every day. She

famously defied soldiers aiming to shoot her by walking straight into their

line of fire without blinking. It became

clear to me that this was someone extraordinary.

What made this remarkable woman

tick, I wondered? She looked like a Vogue model

and had the guts of the American Second World War hero, General Patton. I

became determined to find out more of her story.

How did you

gain access to Suu Kyi? And how hard was it to gain such access?

I travelled to Burma in 2003 while

I was Editorial Page Editor of The Dallas

Morning News. At that time, no press

visas were granted by military authorities and journalists were arrested for

interviewing activists. I worked very

quietly and carefully for nearly a year by long distance to arrange for a

diplomat to escort me into Suu Kyi’s home to interview her. Technically she was supposed to be free from

house arrest at that time, but the reality was that she was harassed by

soldiers or hired thugs at every turn and there was a barrier of armed guards

in front of her home on University Avenue.

Access to her home was restricted, so I resorted to the subterfuge of

accompanying a diplomat.

She proved to be the most

impressive person I’ve ever interviewed, even more intimidating than British

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and more charismatic than many of our American

presidents. We had a thoughtful exchange

for more than an hour. As I left, I

asked her if I could do anything to help her. “Yes, shine the light,” she said.

“Don’t let people forget us.”

Who could say no? After that, I wrote many newspaper articles

about the struggle for democracy and eventually began work on a book, which became

The Burma Spring: Aung San Suu Kyi and

the New Struggle for the Soul of a Nation.

I interviewed Aung San Suu Kyi

again in her home after her release in November 2010 and returned to observe

her campaign for Parliament in 2012. During my trips to Burma over the years, I

interviewed many of the people involved in the democracy movement, including

the venerated journalist U Win Tin, former General and National League for

Democracy stalwart U Tin Oo, 88 Generation leaders Ko Ko Gyi and Min Ko Naing,

blogger Nay Phone Latt, a half-dozen monks involved in the “Saffron

Revolution,” comedian-activist Zarganar, former movie star turned humanitarian

Kyaw Thu of the Free Funeral Service, and many more.

In the US, I also interviewed

former Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright and Hillary Clinton and former

First Lady Laura Bush, all longtime champions of democracy in Burma.

Once you were face-to-face with Suu Kyi, how

did you find her?

She was

extraordinarily poised when I interviewed her, although she was under enormous

pressure as she is now. She poured tea graciously and took care to be a proper

hostess. She has an impressive

presence, a kind of calm charisma that many leaders strive for and do not

achieve.

I found her frank and forthcoming; uncommonly

blunt for a political figure. Unlike

most of our American politicians, who stick to their talking points, she

clearly was listening to my questions and providing thoughtful, spontaneous

responses. Her sharp intellect was immediately evident.

She admits she

has a quick temper and I could see flashes of irritation when I asked her

something she did not want to talk about - such as the pain of being separated

from her children, or past difficulties within the National League for Democracy. She struck me as the kind of introvert who

feels more at ease with books than people, but has to get involved in the “retail

sales” aspects of politics to keep moving the democracy struggle forward. I believe she genuinely feels uncomfortable

having to serve as an icon or “poster girl” for the movement, because that

image seems shallow compared to the difficult and necessary work she is

actually doing. She is acutely aware that others are risking their lives,

working as hard and are equally deserving of the limelight. Yet she understands

the reality that her high profile helps make Burma visible to the world, so she

dutifully subjects herself to interviews such as mine.

One of the aims of The Burma Spring is to address people’s misconceptions about Suu

Kyi. What was your own biggest misconception about her, before you started

researching the book? What did you learn

that most surprised you?

I suppose I was

a bit surprised how well informed she was, considering she had been held under

tight restrictions in her home for so many years. Even though her movements were restricted and

she had limited access to the media, she was keenly aware of events around the

world and inside her country. She has a

well-stocked mind -in conversation, she can quote easily from sources as

diverse as philosopher Karl Popper and Prime Minister Nehru, to Vietnamese monk

Thich Nhat Hanh.

But what really

surprised me was her lively sense of humour. She is quite playful. When I told her I had honed my questions to

20 in case our time was cut short, she laughed and said, “20 Questions? It

sounds like a quiz show.” At one point

she had me take off my shoes to prove she was taller. The story is told that when one of her

colleagues – who had been arrested on his way to a meeting at her house – was

finally released from prison years later, she greeted him at the door with

“Uncle, what took you so long?” She can

seem quite formal in some speeches, but she has an impish side.

Likewise, what were your biggest

misconceptions about Burma, and the Burmese people?

I don’t know

that I had any misconceptions, but I was saddened by the extent of the poverty

and the hardships that people endure.

It’s one thing to read that 75 percent of the people lack electricity –

and another to drive for hours through the countryside and not see any lights

in any of the farm houses along the way. Most villagers were still cooking over

wood fires on the ground and did not have running water or plumbing. It’s shocking to see the number of children

working in tea shops or stirring scalding hot silk pots or raking through the

rubble in mining areas. I travelled to

the Delta area that was devastated by Cyclone Nargis and talked with many

people who had nothing left – not even a roof over their heads – and yet they

were kind and hospitable and polite.

What about accurate preconceptions? Did you have any of your own preconceptions

confirmed, either about Suu Kyi, or about Burma, or about the Burmese people?

I knew that

Aung San Suu Kyi was exceptionally brave and had walked through squads of

soldiers who had their rifles aimed at her and her followers in 1988, but I was

amazed to come across many more incidents where her life was in serious

jeopardy. For example, her car was

battered by thugs with pipes and sticks more than once while she was travelling

to campaign events. During a brief

period of release from house arrest in the mid-1990s, she was trapped several

times in her car by soldiers for long periods - once up to nine days - without

adequate food or water. She not only

kept her composure, but stuck to her principles of non-violence and kept going

back out. That is true grace and grit under pressure. She is even braver than many people realise.

Even after scores of her supporters were beaten to death around her during the

Depayin massacre in 2003, she still talked about the need for forgiveness and

reconciliation. That’s extraordinary.

Because Suu Kyi's story is so remarkable, the stories of others who have stood up and spoken up

for freedom are often over-shadowed, so I also took pains to include the

stories of many others who have sacrificed much. This includes student

activists like Min Ko Naing, monks such as U Gawsita and U Gambira, comedians

such as the Moustache Brothers and Zarganar, labour activist Su Su Nway, and

businessman Leo Nichols, who died in prison.

Their stories are equally deserving.

The Burma

Spring

mentions the recent sectarian violence against Muslims, such as the Royhinga,

as well as the on-going attacks in ethnic regions that are largely Christian. Did

you get a chance to discuss sectarian violence with Suu Kyi?

Much of the

violence that has been in the headlines occurred after our interviews, but she

made it clear in our earlier interviews that she is against religious

discrimination of any kind and against violence.

What do you personally think of her

ambivalence to the Rohingya?

She has seemed

to be hedging her bets politically by saying she doesn’t want to take sides

because there have been offences on both sides.

I agree she could have done better.

But she has been consistent in saying she wants to promote

reconciliation rather than take sides and place blame. There have been some reports in the media

that she has said nothing, when actually she has said several times she is

against violence of any kind by either Buddhists or Muslims. She also has

clearly spoken out against the proposals in Parliament that would limit

religious conversion and ban inter-marriage.

So she has spoken out, just not always in a very effective way or the

way some would have preferred.

What do you think will happen after the election later this year?

It’s uncertain whether Suu Kyi will ever get to

serve as President – that’s barred in the current Constitution in Section 59f,

which prohibits someone from leadership positions who is married to a foreigner

or who has children with a foreign passport, as Suu Kyi does. But she will remain a power broker as head

of her party or could possibly serve as Speaker in Parliament if her party

gains more seats in the 2015 elections as expected. Whatever role she plays, she will surely have

to take more positions that will provoke more criticism. Recent history in other emerging countries has

shown that activists who have been the driving force for democracy find their

reputations diminished by political infighting when they assume national office

– such as Vaclav Havel in Czechoslovakia and Lech Walesa in Poland. As Suu Kyi often points out, she is not a

saint, she is only human – and a politician to boot, which means she will have

to make compromises and decisions that will inevitably cost her popularity.

What do you think are the biggest grounds for

worry about Burma’s future?

It is troubling

that journalists are being arrested now and student protests are being shut

down. Land is still being

confiscated. There are legitimate

concerns that powerful elements in the military are loathe to give up their

control to allow for broader representation in Parliament and government

positions. Some believe that those

authoritarian elements –“the hidden hand” – are behind some of the recent sectarian

unrest and they are clinging to profitable relationships with business

cronies. That could lead to more violence

and could result in elections later this year that are not as free and fair as

they should be. On top of that, there

are serious outbreaks of violence along the border region that have exacerbated

tensions with China. It’s a fragile

situation and 2015 will be a critical year.

What are the biggest grounds for optimism?

The investment

that has been pouring into the country is providing needed new jobs and income

for more people, which is like an infusion of oxygen. By some estimates some 500 businesses have

invested USD 50 billion since the economy was liberalised in 2011. Many international non-governmental

organisations are starting to provide health care services, mobile libraries,

environmental expertise and more.

Organisations such as the National Democratic Institute and the Bush

Institute are providing leadership training. Communication is improving – cell phone penetration has gone from less

than five percent to 20 percent in just the last year or so. The resulting information and social media

connections will help inform the population.

Those trends are moving forward and will be hard to reverse, I hope.

What do you hope readers in Asia take from

your book? In particular, what do you hope women readers here take from it?

If Burma can continue

its transition to a market economy and more representative democracy without

more violence, that will be a positive model for other countries struggling

with the constraints of authoritarian governments. The world in general sorely needs a successful

example of dealing with religious and ethnic differences peacefully. Toward

that end, Aung San Suu Kyi’s message of tolerance, forgiveness and

reconciliation are much needed. That is

what sets her apart from most political leaders.

Aung San Suu

Kyi has been an inspiration for many other women in Burma – such as Dr. Cynthia Maung, who provides medical

care along the Thai border; the AIDS activist Phyu Phyu Thin, and new

generation leaders such as Zin Mar Aung.

Women’s groups in Burma have been uniting more in recent months to

combine their efforts on behalf of issues such as discrimination, sexual

violence, and job opportunities. That’s

a positive development since women and children have suffered greatly during

the years of military rule.

Suu Kyi is

living proof that one individual can make a difference if you stand up for your

convictions. Let’s face it, the world is

full of problems caused by human beings.

We need more leaders who will speak up for the noble concepts of duty,

honour, truthfulness, personal integrity, compassion, and service – and mean

it. Suu Kyi may not be a perfect leader,

but she is a necessary voice and her message is one the world needs.