500 words from...is a series of guest posts from authors writing about

Asia, or published by Asia-based, or Asia-focused, publishing houses, in which

they talk about their latest books. Jeffrey Wasserstrom is an American

historian of modern China who teaches at the University of California, Irvine. He

edited a fantastic new reference book, the Oxford Illustrated History of Modern

China. Here

he talks about selecting the illustrations.

Several years ago, when I accepted the invitation

to edit the Oxford Illustrated History of Modern China, which is

already available in the UK, and will be out in North America later in the

summer*, I wasn’t sure about many things. One was which colleagues I

would try to convince to write several of the chapters. Another was what

sort of visuals would be included. I did know two things right from the

start, though, related to a topic, the Cultural Revolution, which has been in

the news a lot lately, due to the arrival of the fiftieth anniversary of its

start. I knew I wanted Richard Curt Kraus to write the chapter on the

topic, since he had just finished a slim, smart, and stylish volume on the

Cultural Revolution for Oxford’s Very Short Introductions series. I also

knew that, if he agreed, I’d encourage him to include a few of the period’s

colorful and varied propaganda posters in his chapter.

Fortunately, Kraus

said yes, and had excellent ideas when

it came to posters, with ones that made the final cut including a vibrantly

hued image linked to Mao’s personality cult and a lovely image of a celebrated

locale known for its oil refineries done in the style of a traditional ink

painting.

Readers of the book will not have to wait until

they get to Kraus’s chapter, however, to see Mao era posters. They will

find some in Stephen Smith’s chapter on the 1950s.

Even sooner, they

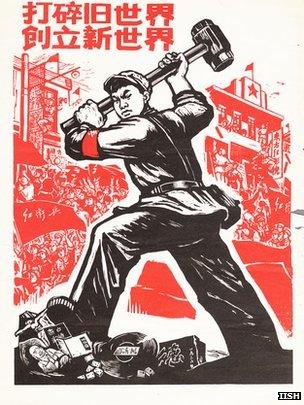

will see in my Introduction a poster

reproduced that was originally created to accompany the Cultural Revolution

campaign to combat the influence of old ideas and practices. This

poster, in red woodblock print style, draws attention to the mix of

continuities and ruptures between the Mao years and the current moment.

The central figure is an outsized Red Guard militant swinging a

sledgehammer, which he is using to destroy, among other things, a statue of the

Buddha, representing the period’s attack on all traditional forms of religion

and philosophy, and a phonograph record - presumably of Western classical,

jazz, or rock music, all of which were disdained by Maoist militants of the

time as bourgeois and decadent.

If we flash forward to the present, we find that

Mao’s successors no longer take a dim view of traditional philosophy and

religion. Confucius was a major focus of criticism during the Cultural

Revolution, yet now Beijing is setting up institutes named in his honor across

the globe. By contrast, there are echoes of the Mao era in the statements

the authorities periodically make warning about the allegedly pernicious

influence of Western cultural imports. Recently, for example, new

regulations came out requiring Chinese television networks to get special

permission before developing programs based on shows created abroad.

Homegrown entertainment is better, the governing body claimed, in promoting the

so-called China Dream, and socialist values - though it is anyone’s guess what

exactly that latter term means in an era of megamalls, showy supercars, and an

ever greater chasm between rich and poor.

* Check

with booksellers in Asia: some may already stock the book;

others may be waiting for it to publish in the USA.