Asian Books

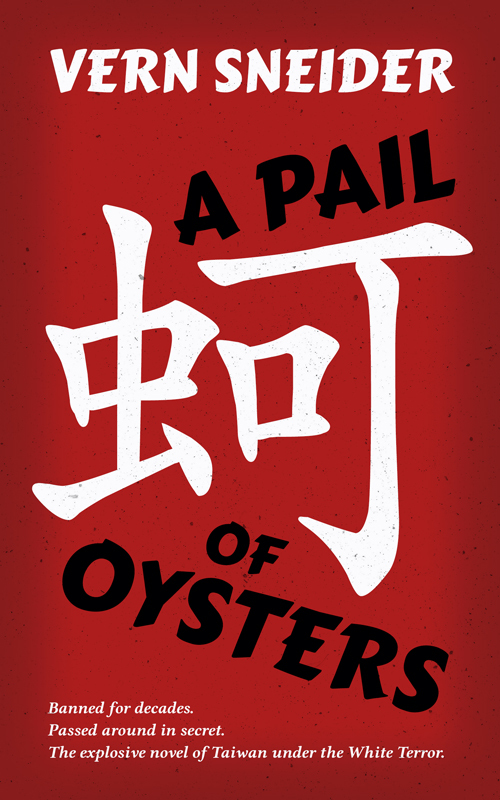

Blog generally covers new books, but in this new series, classics corner, guest

writers will introduce older titles you may like to read. Jonathan Benda kicks

off the series by discussing A Pail of

Oysters, by Vern Sneider

Vern

Sneider’s powerful 1953 novel about martial law Taiwan, A Pail of Oysters, has

recently been republished by Camphor Press

after being out of print for sixty years. The novel received many strong

reviews and was even selected by

the Notable Books Committee of the American Library Association as one

of the 50 books of 1953 which the Committee considered "meritorious in

terms of literary excellence, factual correctness and sincerity and honesty of

presentation". However, it was also criticized by some pro-Chiang Kai-shek

Americans and even condemned as a “thoroughly dishonest book” during a 1954 U.S. Senate

Subcommittee hearing on “Strategy and Tactics of World Communism”. Too

hot to handle during the McCarthy era, A

Pail of Oysters never rose to the level of popularity of Sneider’s first

novel, The Teahouse of the August Moon

(1951), which not only became a bestseller, but was adapted into an

award-winning play and into a motion picture.

What was so

controversial about A Pail of Oysters

that it was so heavily criticized in the United States and banned in Taiwan (a Taipei American School alum recalls

the book being passed around secretly, wrapped in a dust jacket for The Catcher in the Rye)? Through its

tale of an American journalist, Ralph Barton, who becomes involved in the tragic

lives of three young Taiwanese people, the book condemns what Barton calls “the

utter stupidity, the ignorance of a small group who not only enslaved eight

million people, but who endangered all of Asia”. That “small group” is the

faction of the Kuomintang (the Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) led by Chiang

Kai-shek and his son, Chiang Ching-kuo. During his time in Taiwan, Barton comes

to see on a personal level the high costs of U.S. support for the Chiangs’

regime.

Barton’s

Taiwanese friends include a half-Aboriginal oyster farmer named Li Liu; a woman

sold into prostitution named Precious Jade; and her younger brother, whose

trouble settling on his name - he rejects both his Chinese and Japanese names -

mirrors the identity crisis that Taiwan was experiencing after fifty years of

Japanese colonial rule ended and the KMT took over the island. The boy settles

temporarily for the nickname “Didi” (younger brother) until Barton gives him

the English name “Billy.”

Much of the

action in the novel takes place in Taipei, the capital city of the displaced

government of the Republic of China. Li Liu has come to the city from central

Taiwan to look for his family’s god that was stolen from his home by marauding

KMT soldiers. He encounters Precious Jade and her brother, who have escaped

from their adoptive father’s house after Precious Jade ran away from the

brothel to which he sold her. At first, they live by selling Billy’s belongings, including

schoolbooks he needed to prepare for the university entrance exam. Still needing

money to support themselves, the siblings end up working for Barton, and Billy

(the only one among the three who speaks English) and the American develop a

close relationship. Their friendship ends tragically, however, as a result of a

combination of personal revenge and the manipulation of a draconian legal system

put into place by the martial law regime. Barton, sickened by the whole

experience, first considers leaving Taiwan and putting it all behind him, but

is then moved to determine to stay and write to inform Americans about the

regime that is supported by their tax dollars, and Cold War rhetoric.

Despite its

strong criticism of the Kuomintang and its American supporters, Sneider’s novel

is not a one-sided diatribe, but a nuanced character-driven story. Readers are

moved to care about the lives of the characters - even ones with which they

only briefly come into contact. Even the KMT soldiery don’t come off as

completely bad. In one scene, Barton interviews a soldier who had retreated

with the KMT government to Taiwan in 1949. Although the interview is mediated

by Barton’s government-provided interpreter, the tragic tale of the soldier’s

loss of his home and family still comes through to Barton and the reader. The

novel provides enough information for readers to understand political and

socioeconomic conditions in 1952 Taiwan without feeling as though they are

reading a social science treatise or a manifesto. Readers of the novel will

come away from it not only more informed about a period of early Cold War

history that is often glossed over in textbooks but also moved by the touching

story of people whose lives are forever changed by those historical events.

Interest in

Taiwan’s martial law period (also known as its “White Terror” period) has grown

steadily since the lifting of martial law in 1987. A Pail of Oysters developed a reputation among pro-democracy

Taiwanese exiles in the U.S., who saw it as a tale that accurately depicted

their sorrows. It was eventually published in

translation in 2003 as part of a series of works of Taiwanese

literature, but it wasn’t until 2016 that the English original was republished.

Before that, a limited number of editions were available at online bookstores,

but only at very high prices. Recent interest in Taiwan’s postwar experience

has been stimulated by the publication of Shawna Yang Ryan’s excellent novel, Green Island

(Knopf, 2016). A Pail of Oysters,

written toward the beginning of this era, provides interested readers another

emotionally powerful perspective on this period.

About

Jonathan Benda

Jonathan Benda is an associate teaching professor in the Writing Program

at Northeastern University, Boston, USA. Previously, he lived for 16 years in

Taiwan, where he taught at Tunghai University in Taichung. His publications

include the introduction to the new Camphor Press edition of Vern Sneider’s A Pail of Oysters.