'Burma’s Siberia’ is dedicated to K Za Win, one of two poets killed when the military opened fire on civilian protestors last March. Another poet Khet Thi, who had read a rousing poem at K Za Win’s funeral, was later abducted from his home, and died in police custody. This poem was written less than two weeks after K Za Win’s death, as the wider literary circle was still reeling from a series of losses. Its author, Kyi Zaw Aye, was a friend of K Za Win’s who had hosted him in his house the night before he was shot. “Never once / the world is on our side”, it begins, “We unfurl our own flag / we unfurl our own sail / always against the wind”.

There is a palpable sense of being left behind, failed by the world’s broken promises. “Don’t look out for / a pretender to the throne. / Don’t count on a saviour” writes Kyi Zaw Aye, lines that echo Ukranian president Volodymyr Zelensky’s frustrated statement early on Friday morning that “we are left alone in defense of our state”. There is pain, of course: “Tragedy is that / the mother earth has lost a poet / who will write her history”. But there is also something like hope, that signals itself in a crucial turn in the poem’s last stanza: “And still –”

who dare say

he won’t come back

like Latwe Thundra, or

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn?”

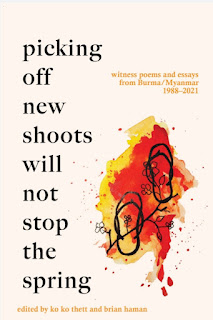

‘Burma’s Siberia’ is one of forty-five pieces in the anthology’s first and most substantive section, all of which were written in the wake of the coup in Burma/Myanmar in February 2021. These grew out of a core of writing shared with the editors via PEN Myanmar in the early days of the crisis, and go on to record scenes of regime change and revolution in heady, and sometimes horrifying, detail. The anthology’s title comes from an essay in this section, inspired by words on a placard brandished by teenage protestors against the junta. “They look determined”, observes Ma Thida, the author of this eyewitness account (also a former prisoner of conscience and board member of PEN International). “They don’t believe in anger or sadness, but they do believe in hope”.

For many contributors, though, anger and sadness are the predominant reactions. Who can blame them? As poet Zeyar Lynn laments in the anthology’s blistering opening pages, “It’s the year of the ox. We are boxed oxen billed for the kill / […] / The bullet blows your life off”. Violence has hemmed them in, and no-one seems to have a solution: “I’d rather the world not issue statements; / Let us be killed in peace” (‘Myanmar’). Others, like Moe Way – publisher of The Eras Books in Yangon – are more philosophical. “Like gemstones / the spirit outshines / the barricade bomb blasts”, he muses. “The spirit body is the spirit. / The spirit breath is the spirit. / The spirit flag is the spirit” (‘The Spirit’).

Especially prominent in this section are writers from the Rohingya community, whom the editors note have suffered some of the “most hideous examples” of inequality and persecution, and who, like many Ukranians in the past week, have had to flee their homes. One writes under the pseudonym of “Dialogue Partner”, scornful of paper-thin efforts to protect her people: “Time and again, / you ‘demand’ and you ‘urge’ / they respect our rights, whatever” (‘Two words I hate most’). Another is Thida Shania, a member of the Art Garden Rohingya collective. In a deeply moving poem framed as a series of questions and answers, she asks: “Where can I hide my body? / Corpses, everywhere in every house”. Surrounded by danger, and with nowhere left to turn, this catechism of loss is all she has. “Why does the sun look desolate? / There is twilight without dawn” (‘An ox for a wad of paan’).

The later sections of the anthology contain pieces from two distinct time periods: the decade of comparative openness that Burma/Myanmar experienced from 2010-2020, and the years between the 1988 uprising and the election of a civilian government in 2010. By sequencing the anthology in reverse chronological order, the editors gesture towards what they see as the “temporal, economic, moral and political slippage” that the country has undergone. For the reader, this creates an eerie sense of déjà vu, as if inklings of the destruction that is to come could already be seen in days of relative peace. One standout poem – based tellingly on an image of a coffin standing “in an elevator / going down / in a high-rise” (‘Elevator’) – was first published in 2015 by the poet Han Lynn, when Burma/Myanmar was enjoying a newfound, if cautious, prosperity. In 2021, Han Lynn was seized and jailed in the same month of protests, when K Za Win and others lost their lives.

I thought for a long while about whether it would be appropriate to review this anthology in light of the last forty-eight hours. To be clear, the contexts are vastly different. Three weeks ago, when I picked up my copy from the Ethos Books office, and leafed through the pages for the first time, war in Ukraine still seemed improbable. But now it is impossible to read the poems and essays here, whether from before or after the February 2021 coup, without the ongoing conflict in mind. This is what literature does, after all: it finds us in the world, this burning world. And whether it is against the backdrop of unexpected wars, or brutalities of a more commonplace sort, it reminds us that the worst – and best – of what we otherwise find difficult to imagine are less remote than they seem.

***

A nonprofit publication, picking off new shoots will not stop the spring is available from Ethos Books (Singapore), Gaudy Boy (US) and Balestier Press (UK).

Read more about the crisis in Burma/Myanmar, and writers caught in the conflict, in this essay by Lucas Stewart for Asymptote. You can also read an essay by ko ko thett, one of the anthology’s editors, on translating the poem ‘Hlaingthaya’ by Thitsar Ni, at the National Centre for Writing website here.

Theophilus Kwek is poetry editor of the Asian Books Blog.