Guest post by Laura Jane Lee

Daryl Lim Wei Jie’s sophomore collection

Anything But Human is a provocative incantation of sensations and sensuality, of detritus and the mundane. The volume hails a marked departure from the poet’s momentous first collection,

A Book Of Changes, landing it more on the irreverent, tongue-in-cheek side of things, as poetry goes.

Anything But Human takes its title from Wang Xiaoni’s poem ‘A Rag’s Betrayal’ (一塊布的背叛), in which she writes, “Only humans want secrecy / now I’d like to pass myself off / as anything but human.” (trans. Eleanor Goodman). With this epigraph and title, Lim ushers the reader into an immersive vignette of objects made strange. Amongst these are snapshots which one perhaps can only describe as “delightfully unpleasant” – an oxymoronic feat within itself – evoking incomprehensible sensations in the reader’s body with lines such as “The cough caught in my / throat flowers into a bulbous alien fruit”. Lim’s poems boldly traverse regions of distaste and pleasure, a pleasure rooted in physicality skirting but narrowly avoiding the sexual; as when he writes “They call me a daughter of disorder. See you / at the dungeon later, dry but preferably wet.”

Another prominent theme of Lim’s poems is the thrill of lush decay, speaking of compostable orchids and orangutans, richly marbled and melting sleep, and silverfish unmaking knowledge out of circulation. These are poems which run rife with the postapocalyptic stench of late capitalism, in both the domesticity of the compliant toilet and the dying oranges in the fridge; to the Costco-like supermarket of ‘Junkspace Rhapsodies’. Not only does Lim conflate the mundane and the grotesque (which are often not so different). In the poem ‘Cloisters’, he invokes the toasts bearing images of Christ and the Virgin Mary fetching exorbitant prices on eBay, and in doing so juxtaposes food, spirituality, and capitalism, arguably the primary non-human mainstays of contemporary society. While these brilliant and humdrum idiosyncrasies running throughout the book easily set Lim apart from most of his contemporaries, it is also against the backdrop of such deftly woven paradoxes that his inventive reinterpretations of Bai Juyi pale in comparison. The lacunose translations seem to lack the same urgent yet languid flippancy of Lim’s original poems, and would perhaps find a better home in a separate volume of similarly reinterpretive poems.

These shortfalls are few and far between, largely outshone and more than redeemed by the experience that comes with reading the rest of the collection. The reader is served enthralling sensations of putrefaction alongside slices of the quotidian, societal observations of the variety seen on SINGAPORE ON PUBLIC NOTICE (@publicnoticesg), as in ‘Narrative (II)’, in which the persona asks permission to pee on insects before doing so, and closely observes the plastic packaging growing out of bushes. One wonders if Lim is the very prophet he writes of in ‘The Prophet’s Day Out’ (for Wong Phui Nam) and ‘The Prophet’s Last Warning’; the reader can’t help but notice that the collection, written pre-pandemic, speaks of occurrences such as “Parliament is closed today, but so are / the KTV lounges” and “The air-conditioning doubles as disinfectant… The air-conditioning doubles as reinfectant”.

For all the simultaneous sharpness and listlessness of his poems, Lim’s Anything But Human features lines of strange, shaking tenderness, all nestled amongst the debris. For visceral human emotions to feature amongst things which are “Anything But Human”, is for them to be heightened and distilled to a singular shade of essentiality and desperation. Equally interesting is the handful of lines strewn carelessly across the poems, which provide a provocative political commentary, issuing from the mouth of what seems to be a half-hearted commentator. Anything But Human is not without surprises – it is at turns most ostensibly human.

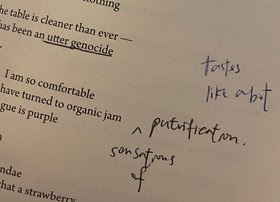

Upon this reviewer’s first reading of the collection on the MRT line, somewhere between Tan Kah Kee and Chinatown, she scribbled the following comment beside the first poem, ‘Expression of Contentment’:

|

| "Tastes like a bot" |

Perhaps the comment would now be better revised to: “Tastes like a bot, but is not.”

***

Laura Jane Lee is a poet from Hong Kong, currently based in Singapore. Under her former name, she founded KongPoWriMo, Subtle Asian Poetry Collective, and is the winner of the Sir Roger Newdigate Prize.

Her work has been awarded in various international competitions including the Oxford Brookes International Poetry Competition, Out-Spoken Poetry Prize and the Poetry London Mentorship Scheme, among others. She has been published and featured in journals and newspapers such as The Straits Times, Tatler Asia, HKFP, HK01, QLRS, ORB, and Mekong Review; and will be reading at the 52nd Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Read a review of Laura Jane Lee's 'flinch & air' here!