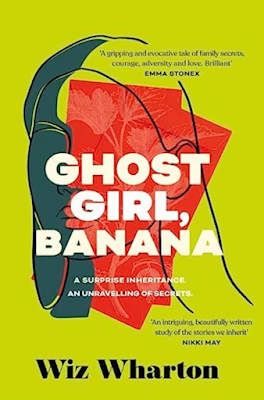

About the Book:

Set between the last years of the “Chinese Windrush” in 1966 and Hong Kong’s Handover to China in 1997, a mysterious inheritance sees a young woman from London uncovering buried secrets in her late mother’s homeland in this captivating, wry debut about family, identity, and the price of belonging.

Hong Kong, 1966. Sook-Yin is exiled from Kowloon to London with orders to restore honor to her family. As she strives to fit into a world that does not understand her, she realises that survival will mean carving out a destiny of her own.Thirty years later in London, having lost her mother as a small child, biracial misfit Lily can only remember what Maya, her preternaturally perfect older sister, has told her about Sook-Yin. Unexpectedly named in the will of a powerful Chinese stranger, Lily embarks on a secret pilgrimage across the world to discover the lost side of her identity and claim the reward. But just as change is coming to Hong Kong, so Lily learns Maya’s secrecy about their past has deep roots, and that good fortune comes at a price.

Heartfelt, wry and achingly real, Ghost Girl, Banana marks the stunning debut of a writer-to-watch.

About the Author:

|

| Wiz Wharton, Courtesy of Author |

_________________________

EC: Congratulations on your debut novel, Ghost Girl, Banana, which has just launched to much critical acclaim in the UK. In your acknowledgement, you mentioned the story’s inception as ‘the discovery of some old-fashioned floppy discs in a box’. Can you tell us about how a whole novel was borne out of this discovery?

WW: Yes, so this happened back in 2020 when I was moving house and discovered the discs in a box of my late mum’s possessions. Initially, I had no idea what they were, and it was only later that I discovered they were transcriptions of her diaries, kept since she arrived in the UK in the early sixties as an immigrant from Hong Kong. Although painful to read in parts, they were also transformative in revealing so many of her experiences which she had never really spoken about during her lifetime. That stoicism is germane to many women of that generation, I think, as much as it’s also a cultural thing, but I remember wondering how many other hidden stories there were out there, and what a tragedy it was that they weren’t more represented in the British fiction space. As much as a novel is always an ambitious creative project to embark upon, I had a whole wealth of information in front of me to draw upon, so I was very fortunate in that respect.

EC: I imagine the process of delving into such personal history must not have been easy. What has the process of writing the novel been like?

WW: Obviously, there were all the usual insecurities that authors go through - is it any good? Will anyone want to read it? Will I ever finish it? I’ve been writing for quite a long time now, and that imposter syndrome never quite leaves you, not least because each new project feels like you’re starting from scratch. It didn’t help that I’d chosen a particularly ambitious dual timeline/dual narrative structure, either! But of course, there were specific challenges to writing such a personally inspired book and I’ve spoken quite a lot recently about art and responsibility. Putting your work into the public sphere is always a vulnerable act, but when it’s informed from a very real place you have to be mindful, both in terms of self-care and the care of others who might one day read it. That’s not to say that your truth isn’t valid, but simply that you can’t be exploitative in that truth which is why I chose to write a novel rather than a memoir.

Throughout the process, I’ve been extremely lucky in terms of the people I’ve had around me - agents, editors, friends and family - who have all championed the book from its early stages. There’s a much stronger movement now towards own voices that wasn’t around when I first started writing, and that’s been wonderful to see, even though we aren’t quite there yet in terms of true equality of representation.

EC: As you said, there was a dual narrative structure, viz, the two alternating perspectives in the book: Lily in 1997 (daughter) and Sook-Yin in 1977 (mother). Tell us why you decided to structure it this way, and was it hard to keep their voices distinctive?

WW: When I first began the book, I fully believed that it would be Sook-Yin’s story exclusively. It was only about halfway through the first draft that I started to reflect on the parallels with my own journey growing up - the attempts to assimilate both sides of my cultural heritage - and came up with the idea of doing a dual narrative/timeline. As soon as that moment happened, the whole novel really opened up to me and became much more about the generational legacy of trauma and secrets within families. I built in so many thematic and visual mirrors on the back of that creative decision, because as much as Lily has a lot more choice in her life in terms of her gender and economic/sexual freedoms, the issues around her identity and belonging endure. I thought that was such an interesting dynamic to explore, not least because it’s a reflection on how far we still have to go in society in terms of acceptance and tolerance of otherness.

Keeping the voices distinct was very much helped by the thirty-year difference that separates the women and the fact that Lily was born and raised in the UK. Of the two however, Lily was definitely the most challenging to get right. Part of this came from handling her strand in first person which for me is always the most intimate point of view. It requires a willingness to be especially vulnerable, a fearlessness about mining those dark places in your own experience in order to be emotionally authentic.

EC: I’m intrigued that you mention Lily’s personal history and how it parallels with your own. In fact, Lily’s search for personal history, identity, and lineage also dovetails poignantly with the Handover of Hong Kong. I especially love that one moment you describe of Lily watching the pomp and solemnity on TV – the moment the Union Jack was lowered, but the Chinese standard hadn’t yet been raised, and Hong Kong for that few seconds ‘belonged to nobody’. This juxtaposition really folds the personal within the collective, and I’m curious as to how you see national identity and history influencing personal identity and history for your characters.

WW: I’m so glad you asked this! For me, the whole essence of the novel is about that search for identity and belonging, but also how we define the word “home”. Is home an emotional or a physical state, and who decides this? The central tension for most of the characters in the book is “I want to belong but I also want to be true to myself” but that’s especially pertinent for Lily and Sook-Yin, who go from a place of having their identities defined by others to a position where they are defining themselves - as women, as sisters, as daughters, as both not half. In the same way, Hong Kong was for decades defined by its colonizers, for good and for ill, and there are some people who welcomed its return to China and the erasure of that indentured history. But for a lot of the younger generation now, Hong Kong is its own thing. Territories may exist as possessions in the eyes of the law, but the people within them are much more than their perceived nationality; they are the sum total of their experiences and their beliefs and their cultural legacies which may be drawn from a whole gamut of influences.

EC: Food depicted strikingly in two places reminds me of how integrally tied it is to not just identity but also the idea of nourishment and refuge (when Sook-Yin’s brother in law brought her red bean paste buns in the hospital after she gave birth to Lily), belonging and identity and a sense of home (Sook-Yin’s happiness in sharing a sumptuous meal of rice and rainbow trout, choy sum, bitter melon with dried shrimp with her friend’s family). Why do you think food brings out so much cultural meaning?

WW: When I was growing up, food was the sort of love language of our family and I think this is something very common to many cultures around the world. It’s not only a marker of both identity and memory, it’s often our first experience of being nurtured by our loved ones and so yes, in the book it represents familiarity to Sook-Yin and an anchor to everyone and everything she has left behind. There’s a passage later on where she tries to cook moo-shu pork for her English husband’s family and their rejection of it is a metaphor for their refusal to accept her in many ways; a sort of fear response of losing their own identities by eating it. Similarly, Lily’s appetite and willingness to try the unfamiliar food of Hong Kong is, in part, a desire to reconnect with her late mother, to absorb her through that potent emotional currency.

EC: I want to talk about the men in this novel. Sook-Yin’s husband emerged as weak; Sook-Yin’s brother cruel, and even the love of Sook-Yin’s life, though true enough in his affections, cowardly. The effect though is to bolster the women’s quiet strength and dignity. Was this intentional?

WW: It’s very true that the focus of the book is on the quiet strength and resilience of its central women, something which for Sook-Yin’s generation was rarely acknowledged, or only through the usual markers of success such as wealth, a fortuitous marriage or educational attainment. But it’s also true that Lily is undervalued in the novel for similar reasons, especially when compared to her older sister Maya, so it’s not entirely a gender-based bias.

I do agree however, that the men are by and large pretty horrendous, although I hope people can also read them through the lens of history and culture. Many societies were, and still are, patriarchal by definition and the onus on men to be the breadwinner and decision-makers of the family was ingrained by their elders. It would have been incredibly emasculating for men of that time to be outshone by their wives or sisters, emotionally or materially. Daniel represents a younger generation of men who want to be seen as more hopeful and less regressive in that regard. It’s incredibly interesting to me that older readers have been much more accepting of the status quo reflected in the novel whilst younger readers have been totally outraged, but to me this is the beauty of reading books; that everyone comes to them with their own individual experience.

EC: What has been the best thing for you about writing this book?

WW: The very best thing has been staying true to my original intentions for it, which was to shine a light on the hidden women of my mum’s generation and to pay tribute to their incredible and unacknowledged contributions to society. My mum passed away very suddenly and I was unequipped emotionally to say everything I wanted to in the immediate aftermath. I hope that the novel redresses that imbalance.

The other – totally unexpected – result of writing the book is that it went to auction for the adaptation rights last year and that I’ve been invited to adapt it as a limited series for television. Before turning to long-form I was a screenwriter and so it feels as though my life has come full circle to some extent. I’m currently writing the pilot episode and we’ve already had interest on the back of the book, so fingers crossed that it gets picked up!

By far the best consequence, however, have been the messages from readers thanking me for writing something in which they finally feel seen. Nor has this been limited to British-born Chinese readers or readers of mixed east or south-east Asian heritage, but also those from other diasporas now living in the UK. As someone who never saw themselves reflected in the mainstream fiction space growing up, that is honestly the greatest privilege I could ever hope to have.

NB:Ghost Girl, Banana is available worldwide at all local stores at local prices. Support your independent stores!