Guest review by Daryl Lim Wei Jie

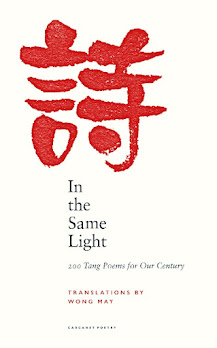

Wong May, the poet behind

In the Same Light, a collection of two hundred Tang Dynasty poems in translation, is something of a legendary figure. Born in Chongqing, China during the Second World War, she subsequently moved to Singapore with her mother and siblings. After being involved in the fledgling poetry scene at the University of Malaya (now the National University of Singapore), she moved to America, attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from 1966 to 1968, and published three remarkable poetry collections in America, under the Harcourt imprint. She moved to Europe in the 60s and now lives in Ireland; according to the biography in this book, she paints under the name Ittrium Coey. In 2014, her fourth collection of poems,

Picasso’s Tears, was published after a silence of 36 years.

Wong’s migrations were on my mind as I read this book, which is subtitled 'From the Migrants and Exiles of the Tang Dynasty'. After all, the sense of belonging to a Chinese diaspora, and the complexities of that position, ties us – Wong , myself, and many others. (When Wong writes about “us” in her

Afterword, it is clear she means and identifies with “us Chinese”). Wong can be situated in a long tradition of diasporic writers who have written poetry primarily in English, but have productively engaged with the classical Chinese tradition. (Malaysian poet Wong Phui Nam and his

translations of the Tang poets come to mind, as do Singaporean Joshua Ip’s perverse anti-translations in his recent collection

translations to the tanglish, and this reviewer’s own

adventures with Bai Juyi.) As China increasingly enters the imagination of the West, sometimes on its own terms, and too often as lurid phantasm, one wonders if Chinese diasporic writers are drawn to Tang poetry as an act of cultural ambassadorship – not necessarily for China, but for broader Chinese culture(s). At the very least, China’s growing prominence seems to have sparked some introspection and (perhaps I speak for myself here) a desire to rediscover this heritage on our own terms.

It may be unusual to begin a review by focusing on the translator. But one cannot help but notice Wong’s presence, even as she repeatedly disclaims it in the Afterword: “The translator should ideally be the missing person”, she writes; and elsewhere, “Poetry is what requires no translation”. Yet this extraordinary Afterword, titled ‘The Numbered Passages of a Rhinoceros in the China Shop’, is a magnificent, peculiar tour de force that spans nearly a hundred pages, and the book is transformed by its existence. It is probably why you should buy this book. In fact, I’d recommend that any reader start there, because the translations are imbued with fresh significance after the Afterword.

It is the key to the book; it is also somewhat beyond summary. In some ways it is a frenzied guided tour of a quixotic memory palace-museum like no other: Wong tells us about the Tang poets she translates, and offers interpretations and appreciations of their work. She also provides snippets of her own life; we learn that her mother was a Classical Chinese poet, and that the noted Singaporean calligrapher and poet Pan Shou was a familiar presence in childhood: “Uncle Pan, in whose voice I first heard Du Fu’s”. She curates imaginary display cabinets to accompany the poems: one, labelled ‘Specimens’, has “Cliff honeycomb, winter bamboo shoot, purple taro & corn, fiddlehead greens, vetch and wild chestnut. Foraging with Du Fu on the famine road.” Ezra Pound, that false friend of the classical Chinese poets, makes an appearance, of course; so does an interpolating illustrated rhinoceros figure, who provides laconic commentary on the Afterword. She discusses repeatedly a philosophy of reading and understanding poetry, exemplified in the Chinese words 入神 (rù shén) and 出神 (chū shén), the former meaning “to enter the spirit” and the latter meaning “to exit the spirit”. When reading, we are told, “one enters the world, or the world enters you.” At the end, we are ushered into a gift shop, where the Tang poets and their poems are paired with Western artists on souvenir tea towels, all of them “Made in China”. Here’s one: “Blue fields. Warm sun. Smoke rises where jade lies buried. Fat of some land. The blue fields of Li Shangyin shall always be Van Gogh, smoke semaphoring in cross stitch needlepoint kit, colour threads included”.

One cannot help but beguiled by this performance: it’s entrancing, and entirely sincere. At times it overpowered my own scepticism about Wong’s easy comparisons between the Tang poets and the Western canon, such as parallels between Li He’s poetry and Keats’ La Belle Dame sans Merci, or King Lear and Wang Wei’s poetry. Perhaps more generally, as an Anglophone writer from Singapore who still feels with some heat the distinctions between the centres and peripheries of Anglophone writing and publishing, I am unable to agree to Wong’s proposition that the translator’s task is simply to “return the text to the body of world literature, the world in which all have our origin”. I can only aspire to such ecumenism, but my experience speaks against it, my heavy awareness of distinctions drawn repeatedly between the “local” and “international”.

Moving to the translations themselves, one immediate question is: why this selection? In terms of the poets chosen and the number of poems translated, weight is given to the conventionally well-regarded, such as Du Fu, Li Bai, Wang Wei, Meng Hao Ran, Bai Juyi and Li Shangyin.* (Some others have just a single poem featured.) Du Fu’s selection is the most extensive, and sheds light on Wong’s intentions in selection: poems of exile and wandering, as well as poems about Du Fu’s well-known friendship with Li Bai, feature prominently.

In the Afterword, Wong remarks that “In China … the image of the poet is indissolubly linked with exile.” The exilic condition of the Tang poet has been celebrated for centuries: the poet miles away from his family and home, due to war or banishment; who struggles to find home; who finds home in friendship with other poets; who finds home where there is poetry and wine. It is perhaps no surprise that emigrant writers, and in particular, the Chinese diaspora, have found Tang poetry so emotionally resonant. (We see this in Wong’s own concerns: her haunting poem ‘Sleeping with Tomatoes’ documents the tragic plight of fifty-eight Chinese migrants who suffocated in a van while being trafficked.) A poignant demonstration of this exilic condition is provided by the first poet featured, Liu Zongyuan, in Wong’s translation:

Troubled by

little

Today

Haply

a guest

Am

I

The

tree haply

My

host.

In the translations of Du Fu’s numerous poems to Li Bai, Wong achieves a perfect balance between lament, longing and love:

A thousand autumns –

We can cope with.

& yet

& yet to deal with the paraphernalia

Of this life

As if one were dead,

Friend,

How

friendless is that.

Another

theme is poetry itself as a subject, as shown in this Bai Juyi poem:

So my verse takes me

Far from the world’s mockery

Singing

madly

To the mountains

Poetry,

It worries me.

Also

notable are two rare female Tang poets: Yu Xuanji and Xue Tao. Across the

centuries, Wong May, herself a pioneering female poet, gives voice to Yu

Xuanji’s frustrations and impossible ambitions as she looks at a list of those

who have passed the civil service examinations:

&

how I hate the clothes

I stand in,

The cloth they are made of.

They

cover up much.

A woman’s poems too

Are something to hide?

Poetry alas,

& much more besides.

Lifting

my head

I went through

The list of names

With plain envy.

Much of

the striking verve of these translations can be credited to Wong’s style, and I

would like to point out three aspects of this method: the use of space, the

freshness of voice, and the willingness to go beyond the text.

The

first is well-demonstrated by the examples above: space restores to Tang poetry

the necessary emphasis and significance of each character, much harder to

achieve in English. If we look again at Liu Zongyuan’s poem above, and compare

it to another translation below, it is the inspired use of form that

brilliantly conveys the forlornness of the scene, and restores emphasis to the

two key words in the second line quoted here: 宾 (“guest”) and 主 (“host”).

On the second point, Wong often draws the Tang poets far closer to us through colloquial diction, such as in (yet another) Du Fu poem about “Not Seeing Li Bai”:

Am I alone in loving that talent

Goddamn talent

One would wish on no man?

This injection of contemporary freshness brings us naturally to the third point on going beyond the original text. If we revisit Bai’s Juyi poem on poetry (《山中独吟》; 'Singing Madly in the Mountains'), it is clear that the last line in Wong’s translation isn’t present in the original, but it is precisely what provides the translation’s dramatic effect.

Whether this translation aligns with the spirit of the original is possibly a matter of taste, but the surprise achieved by Wong’s startling transmutation of the original is undeniable. (Aficionados of Wong’s poetry may find it reminiscent of her verse, e.g. “Poetry / rots my teeth”.)

I started this review with Wong May, and I wish to go back to her, because she is an inescapable presence in this book.

Wong has been a ghost in Singapore’s poetic canon, and as writers and readers have dug more deeply into our literary history, we rediscovered Wong, who was hitherto barely known, yet right there from the beginning, in the early post-independence years. (Happily, Wong is now featured in the online encyclopedia of Singapore poetry,

poetry.sg.)** As we read, a few of us were increasingly taken, even a little obsessed, with her work, which seemed singular for its time. I found myself buying her out-of-print books second-hand, shipping them from America. One day, my order of

A Bad Girl’s Book of Animals (1969) arrived. It was from a university library in South Carolina and I found, to my astonishment, that it was autographed (and dedicated to Denise Levertov). I am closer to this ghost now, having been one of the first people to have read these translations; having heard Wong May’s voice speak, as if directly to me, in the

Afterword; having written this review. It may be the closest I ever get.

‘Ghost’ is also apt because of the very last poem in this anthology, which is presented as written by an anonymous poet. In fact, the first two lines are well-known in Chinese contemporary culture:

|

君生我未生,我生君已老。

君恨我生迟,我恨君生早。

|

When you were born, I was not yet born; when I was born, you

were already old.

You regret that I was born too late; I regret that you were born

too early.

(Translation mine)

|

Extraordinarily, these lines were discovered on a Tang-era porcelain pot from the famed Tongguan Kiln in Changsha, excavated in the 1950s. The author of those lines is unknown, possibly a folk artist or poet of the Tang dynasty. Yet the remaining six lines in Wong’s translation are not from the original, but apparently a continuation by a contemporary Chinese poet, Cheng Dongwu. (Mysteriously, this is also the only poem which has the text in the original Chinese.) It is oddly fitting that this last poem, which bridges all the other poems and the Afterword, is in part by a contemporary author. That famed injunction by Ezra Pound, by way of Emperor Cheng Tang of Shang’s washbasin, comes to mind, an abiding inspiration and warning to future readers and translators of the Tang poets – “make it new”.

Notes:

* A minor kvetch: one would have expected an internationally renowned publisher like Carcanet to have taken greater care with the editing, yet inconsistent and incorrect spellings of the poets’ names are rife: Meng Hao Ran is variously spelt “Meng Hao Ren” and even “Meng Haran”, for example.

** It may be instructive to compare her story and reception with that of another poet in a similar position, Wong Phui Nam, the pioneering Malaysian poet who was referenced earlier. In addition to sharing a surname and an interest in Tang poetry, both have, until recently, been written out of the history of Singapore literature in English, despite having been pioneering figures in the scene whilst studying in the University of Malaya in the 1950s and 60s. Like Wong May, Wong Phui Nam is also drawn to the exilic condition of these poets.

***

Daryl Lim Wei Jie is a poet, editor, translator and literary critic from Singapore. His first book of poetry is A Book of Changes (2016). He is the co-editor of Food Republic: A Singapore Literary Banquet (2020), the first definitive anthology of literary food writing from Singapore. His latest collection of poetry is Anything but Human (2021). His poems won him the Golden Point Award in English Poetry in 2015, awarded by the National Arts Council, Singapore.