I've decided to try to offer listings of literary events across Asia, excluding West Asia / The Middle East, but extending west to east from the Indian Sub-continent to Japan, and north to south from Mongolia to the southern tip of the Indonesian archipelago.

I will accept listings up to three months before the event takes place. If you would like to have an event included please e-mail details to asianbooksblog@gmail.com. Please state the month of the event in the subject line, and specify that this is a listing, e.g. September / listing. Please provide the following information:

Date of event

Nature of event and a brief description. E.g. book launch plus a 100 word description

Venue for event with both a complete real world address, and a link to the venue's website / details of its Facebook page if these are available

Cost of event, if any, plus details of discounts, if any

Language of event

For booking and further information please contact...followed by relevant information

For a series or a course of events at one venue, or for literary festivals at multiple venues within one general area, please supply the start and finish dates. For literary festivals, I will give only the over-arching venue, e.g. Jaipur, Hong Kong, or wherever.

I have also decided to launch a book club. I will select a book at the beginning of each month, and request that people post comments through the month. I will then summarise these at the end of the month, plus give my own thoughts.

My first book club selection, for September, is Crazy Rich Asians, by Kevin Kwan, a comedy about

three super-rich Chinese families and the gossip, backbiting,

and scheming that occur when the heir to one of the most massive

fortunes in Asia brings home his American Born Chinese girlfriend.

When Rachel Chu agrees to spend the

summer in Singapore with Nicholas Young, she envisions a

humble family home, long drives to explore the island, and quality time

with the man she might one day marry. What she doesn't know is that

Nick's family home looks like a palace, that she'll ride in

more private planes than cars, and that with one of Asia's most eligible

bachelors on her arm, she might as well have a target on her back.

Initiated into a world of dynastic splendor, Rachel

meets Astrid, the It Girl of Singapore society; Eddie, whose family

practically lives in the pages of the Hong Kong socialite magazines; and

Eleanor, Nick's formidable mother, a woman who has very strong feelings

about who her son should - and should not - marry. Crazy Rich Asians is an

insider's look at the Asian JetSet; a depiction of the clash

between old money and new; between Overseas Chinese and Mainland

Chinese.

Crazy Rich Asians is published by Doubleday, in hardback, paperback, audio, and e-book formats. Color Force has acquired movie rights so it should be coming to a big screen near you sometime soon.

So: what do you think? Please do post with your opinions, and I'll share mine at the end of the month.

Sunday, 1 September 2013

Tuesday, 27 August 2013

The Commonwealth Short Story Prize

|

Today, the Commonwealth has 54 members and the Commonwealth

Foundation, a UK-based development organisation, works towards a world in which

every person on the planet is able to participate in, and contribute to, the

sustainable development of peaceful and equitable societies.

Commonwealth Writers is a cultural initiative from the

Commonwealth Foundation. Commonwealth Writers both develops the craft of

individual writers and also builds communities of emerging voices, so that,

individually and collectively, writers can work for social change, and

influence, directly and indirectly, the decision-making processes which affect

their lives. Commonwealth Writers wants the writers it

unearths to inspire others, especially in their local communities, and it challenges

selected authors to take part in on-line residencies, and

on-the-ground literary activities.

Commonwealth Writers runs the Commonwealth Short Story

Prize. This aims to identify talented emerging writers and to promote the best new

writing from across the Commonwealth, thus developing literary connections

worldwide.

The Short Story Prize is awarded for the best piece of

unpublished short fiction, of between 2000-5000 words. The language of the

competition is English. Writers can submit stories translated into English from

other languages.

Entries can be submitted from five regions: Africa, Asia,

Canada and Europe, the Caribbean, and the Pacific. The regional divisions are

intended to give writers in countries with poor publishing infrastructure a fairer

chance to compete with those in countries where there are more opportunities.

Within Asia, you are eligible to enter if you are a citizen of one of the

following countries: Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, India, Malaysia, Maldives,

Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka,

There will be five winners, one from each region. One

regional winner will be selected as the overall winner. The overall winner will

receive £5,000

(approx US$7,750)

and the remaining four regional winners £2,500 (approx US$3,785). Translators of

winning stories will also receive prize money. If the overall winner is a translation into English, the

translator will receive £2,000 (approx US$3,100).

Translators will receive £1,000 (approx US$1,150) for regional winners.

The 2014 judging panel will be chaired by Ellah Allfrey,

deputy chair of the council of the Caine Prize for African Writing, formerly

deputy editor of the UK-based literary magazine Granta and senior editor at Jonathan Cape, Random House, in

London. She will chair an international judging panel; this will make the final

selection. The regional judges will be announced on 1 October. Experienced

readers will assist the named judges in selecting the long lists.

The 2014 Short Story Prize will open for entry on-line on 1

October 2013 and close on 30 November 2013. Entry will be via www.commonwealthwriters.org

where you can view the eligibility criteria, and the entry rules.

So new Asian writers: Get writing! Tell the world what great stories, and what great storytellers, we have on this continent! If you need inspiration, click about on www.commonwealthwriters.org,

it’s a great website, with a mix of interesting tips and advice, discussion,

and constructively provocative comment.

Thursday, 22 August 2013

500 Words From Julian Kim

500 Words From is a series of guest

posts from authors. Here, Julian Kim talks about his first novel, SAINTS:

Song of Winds. This is a fast-paced, multicultural, quasi-historical mystery-thriller that combines a race-against-the-clock adventure, with contemporary concerns about the weather, with a love story, to produce a wild and satisfying romp.

Julian Kim was born in Seoul, but as a child he lived in other places in Asia, as well as in Europe, and in the Americas. Thus from an early age he was fascinated by cultural diversity, and as an adult he continued his nomadic existence, living in New York, London, Hong Kong and Seoul.

Julian Kim was born in Seoul, but as a child he lived in other places in Asia, as well as in Europe, and in the Americas. Thus from an early age he was fascinated by cultural diversity, and as an adult he continued his nomadic existence, living in New York, London, Hong Kong and Seoul.

Julian

now lives in Singapore, where, in 2012, SAINTS:

Song of Winds was the winner of a

competition sponsored by the National Arts Council, to promote the works of unpublished authors. It was subsequently published by Straits Times Press: http://www.stpressbooks.com.sg/home.php

So: 500 words from Julian Kim

So: 500 words from Julian Kim

With SAINTS: Song of Winds I was hoping to

create something which would be fun to write and fun to

read. In addition, I wanted to fuse modern and historical elements of

Asian and Latin American cultures - the core action

occurs mainly in China and Peru, with meaningful scenes also taking

place in Korea, India, Mongolia, Hong Kong and Singapore.

With SAINTS: Song of Winds I was hoping to

create something which would be fun to write and fun to

read. In addition, I wanted to fuse modern and historical elements of

Asian and Latin American cultures - the core action

occurs mainly in China and Peru, with meaningful scenes also taking

place in Korea, India, Mongolia, Hong Kong and Singapore.

As

we all know, our world is full of stories – there is so much

history, so many nations and regions and cultures. Past human

civilisation has left us so many traces - superstitions, fairy tales, legends and myths. Granted, much of this wealth has been lost in the mists of time, but the gaps in our knowledge allow us both to imagine what-ifs, and also to wonder about the borders between fiction

and non-fiction. Without a doubt, Asia offers a vast and rich

depository of history and civilisation from which we can mine and

spin a million what-if factual fictions.

The

same is true for the world of unexplained phenomena. We often hear

stories about the paranormal, about the extraterrestrial, and about bizarre creatures. I think most of us can agree that there's still much that

we don't understand about our planet, the universe, and the realms of

the physical and the spiritual, especially as they relate to the human mind.

So

with all this wealth of secrets and mysteries surrounding Asia and

the world we live in, I could not resist creating a world of somewhat

plausible histories, mysteries and uncommon abilities.

SAINTS: Song of Winds begins two

thousand years ago in China, when a geomancer leads a tribe out of

the tomb of Emperor Qin. One thousand years later, in Peru, the

immense treasure of the Incas is lost to the world. And today, a

strange terracotta soldier is unearthed in the ancient capital of

China.

In my novel SAINTS is an acronym standing for Syndicated Alliance of

Irregular and Talented Specialists. It is a secretive organisation

whose purpose is to save nations, when all else fails. The members of

SAINTS look like ordinary people and behave like ordinary people,

most of the time. But they have very special talents.

There’s

a Korean boy who teaches at school and can secretly control the winds. There’s an American university student who studies

animals and discovers she can heal people. There’s

a young Singaporean billionaire who plays the financial markets and

who possesses an unnatural intuition. There’s an old Mexican man in

Manhattan who sells hot dogs and can see your past. And

they are all connected in a web of fate that stretches from ancient China to the mountains of present-day Peru.

Using

sheer intellect and mastering their subtle supernatural talents, the four heroes join forces with the leader of Peru to free the country

from a mysterious villain who is causing havoc with the weather. But

before they can save the day they must unlock

the cryptic codes of Emperor Qin’s tomb and also find the lost treasure of the Incas. Somehow, they realise, the tomb and the treasure are connected.

In

essence, SAINTS: Song of Winds can be loosely described as a kind of

Indiana Jones meets The Da Vinci Code, in an Asian and Latin American

context. Key events include monstrous battles with lightning and

tornadoes in the desert plains of Peru, desperate scrambles through

deadly chambers in the tomb complex of Emperor Qin, and an epic

cavalry battle between the ancient forces of China and Mongolia.

Labels:

500 words from

Sunday, 18 August 2013

The Documentation Center Of Cambodia

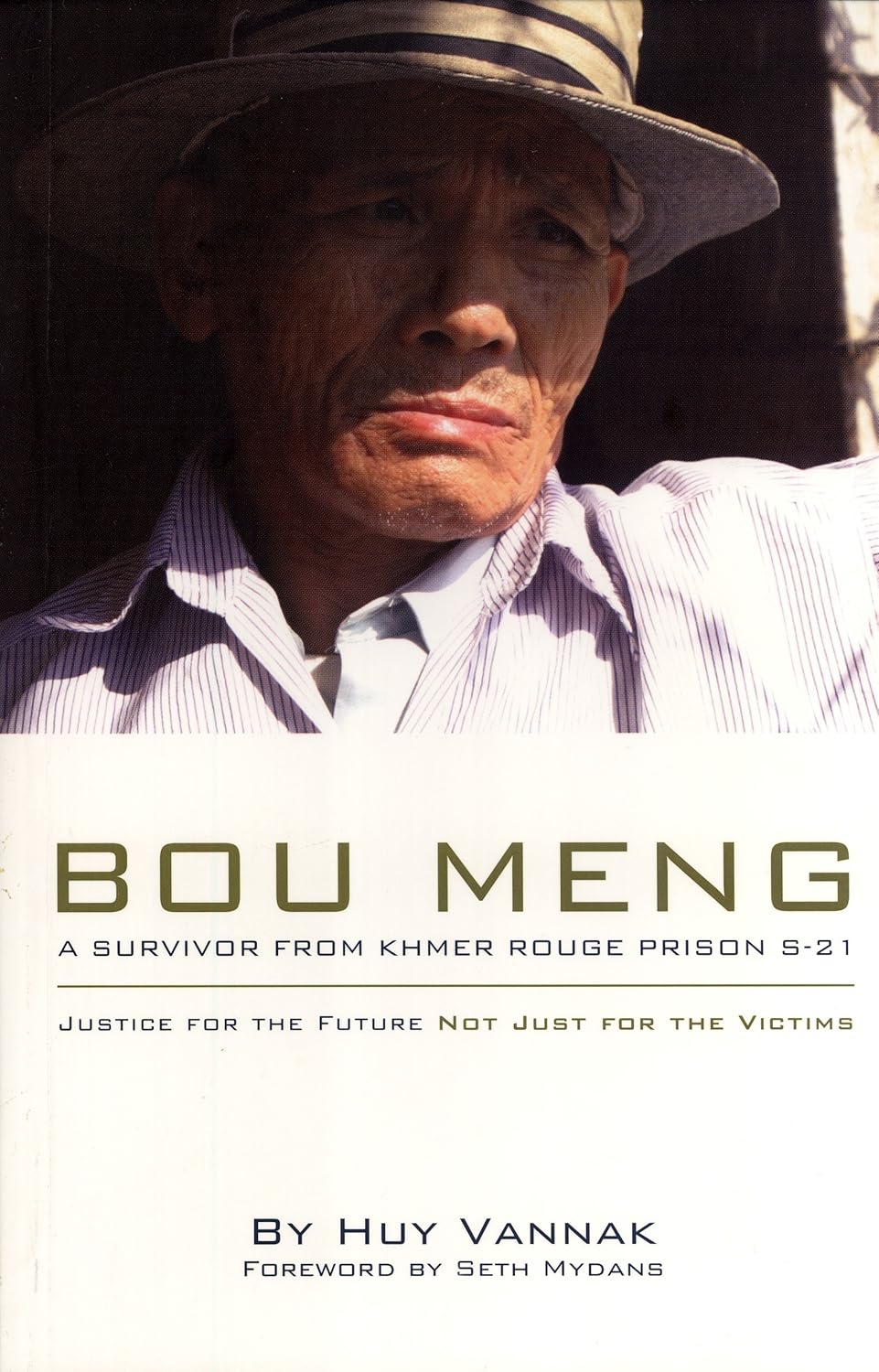

The Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam) in Phnom Penh

enables research into the years 1975 – 1979, when the Khmer Rouge killed almost

two million Cambodians; its dual aims are to record the events of that time to

ensure they are not forgotten, and to bring the perpetrators of great crimes to

justice. The Center presently contains the world's largest archive on the Khmer

Rouge, holding over 1 million pages of documents and 6,000 photographs.

Research undertaken by DC-Cam’s staff and volunteers has

resulted in the publication of many books, including history textbooks and

teacher-training materials for local use. But what about English-language books

for the international general reader? DC-Cam’s director, Youk Chhang,

recommends Bou Meng: a

survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison S-21, by

Huy Vannak, which is published by DC-Cam itself, and The Last One: an

orphaned child fights to survive the killing fields of Cambodia by Marin R. Yann, published by Outskirts Press, and available from their website,

http://www.outskirtspress.com.

Research undertaken by DC-Cam’s staff and volunteers has

resulted in the publication of many books, including history textbooks and

teacher-training materials for local use. But what about English-language books

for the international general reader? DC-Cam’s director, Youk Chhang,

recommends Bou Meng: a

survivor from Khmer Rouge Prison S-21, by

Huy Vannak, which is published by DC-Cam itself, and The Last One: an

orphaned child fights to survive the killing fields of Cambodia by Marin R. Yann, published by Outskirts Press, and available from their website,

http://www.outskirtspress.com.

If you happen to be in Phnom Penh you can buy Bou Meng direct from Bou Meng himself, at the Tuol Sleng Genocide

Museum, formerly the notorious Prison S-21 of the book’s subtitle.

Bou Meng is a

harrowing read. At least 16,000

people were imprisoned and tortured at S-21, of those sent there, only 14

people survived. Bou Meng was one of the 14; his life was spared because he was

an artist, and the regime needed him to paint portraits of the Khmer Rouge

leader, Pol Pot. Bou Meng, who in chapter 2 talks

directly to the reader through Huy Vannak’s translation, is unsparing in his description of

deprivation and torture, both mental and physical. This is typical:

The interrogator kept asking me the same questions. I replied with

the same answers. The interrogator grasped a bunch of torture materials,

including bamboo sticks, whips, rattans, cart axles and twisted electrical

wires. He asked me to choose one

of them. I did not want any of them because they were tools to hurt me. But I

did not have any choice.

Bou Meng’s wife, Ma Yoeun, was killed at S-21, and their

children also perished under the tyranny of the Khmer Rouge. Comrade Duch was

the Khmer Rouge official in charge of S-21. In 2009, a UN supervised trial of

Duch began at a Phnom Penh court; in 2010, he was found guilty of crimes

against humanity, torture, and murder. Huy Vannak reports that Bou Meng now

wants to hold a Buddhist ceremony: “to dedicate justice to the soul of his wife

and the victims of the Khmer Rouge. Then, he believes, their spirits will rest

in a peaceful place.”

Today, Bou Meng paints pictures drawing on his memories of life under the Khmer Rouge. Huy Vannak says: “He draws on his personal memories to paint a collective pain. He hopes his art will inspire the world to prevent a repeat of Cambodia’s painful past.”

In addition to books, Youk Chhang also recommends the movie A River Changes Course, directed by Kalyanee Mam, which follows three families in contemporary rural Cambodia as they struggle for survival, their livelihoods threatened by ever-increasing industrial

development: http://ariverchangescourse.com/

For further information, or to order DC-Cam’s publications, visit http://www.dccam.org/

For further information, or to order DC-Cam’s publications, visit http://www.dccam.org/

Wednesday, 14 August 2013

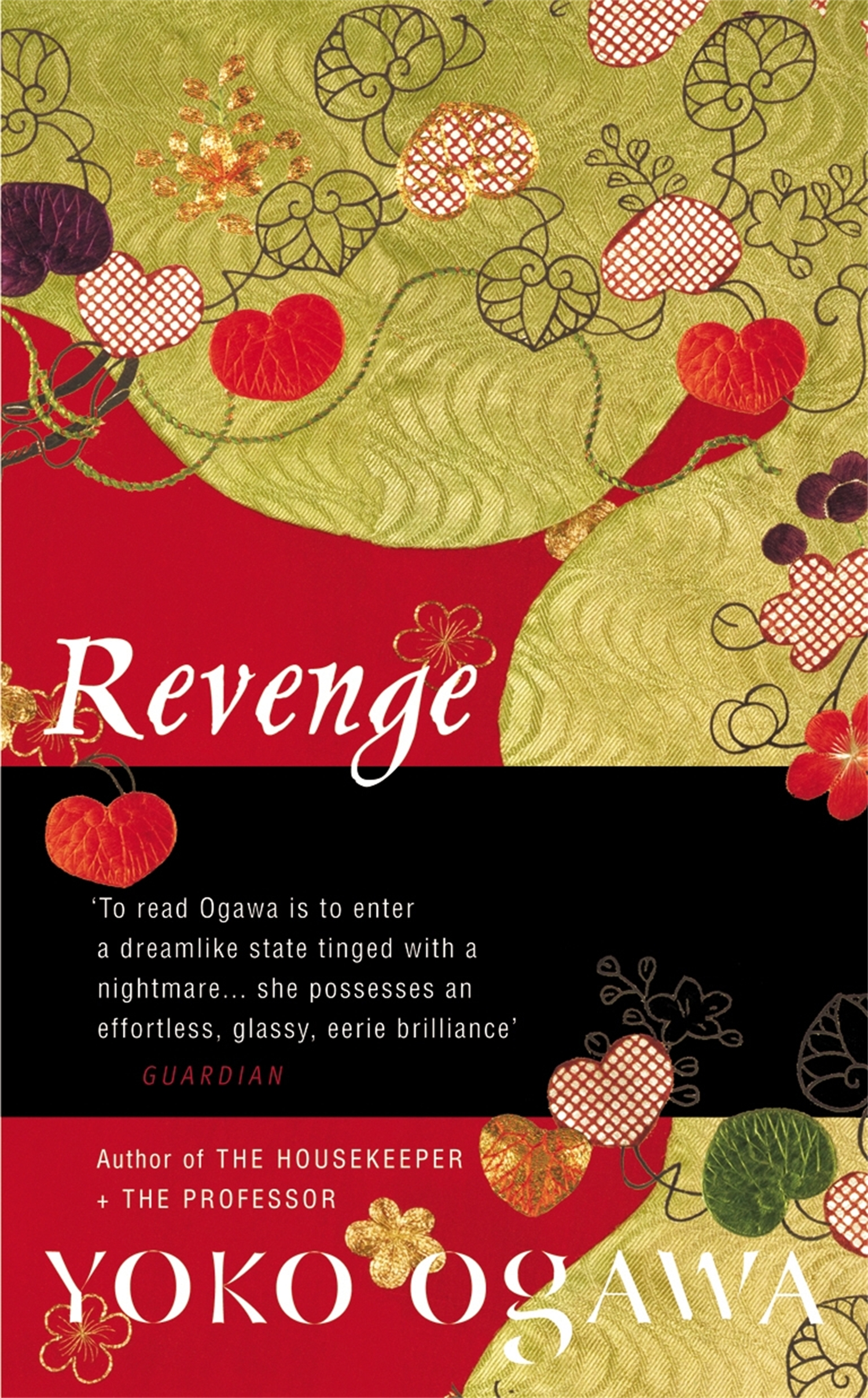

Revenge / Yoko Ogawa

Revenge, by Yoko Ogawa, translated from Japanese by Stephen Snyder, is a mesmerising, weird, and elusive meditation on...what, precisely? Coming up with possible answers to that question is one of the many engrossing challenges of reading Revenge, a collection of eleven short stories, each bound to others by cobwebby chains of connection, and each giving glimpses of the world seen through a most dark-adapted eye.

What few of the stories seem to be about, or at least not obviously, is revenge. Granted, some seem to concern marital, or romantic, revenge: in Old Mrs. J a woman apparently kills in revenge for being trapped in a disappointing marriage; in Lab Coats another woman kills because her married lover prevaricates about ditching his wife; in Sewing for the Heart a bag maker kills because, as he sees it, a customer rejects the bag he has crafted for her, to hold her heart, which lies outside her chest, and hence she also rejects him. But some of the stories seem to have little or nothing to do with revenge. Afternoon at the Bakery, the horrifying first story in which a mother fails to assimilate the unassimilable fact that her child has died in an abandoned refrigerator, seems to be about the way lives can be smashed by improbable, but devastating events; the final story, Poison Plants, which wheels back to Afternoon at the Bakery through the "motif", if that is what it is, of a dead child in an abandoned refrigerator being found by an old woman, seems to be about the loss and degradation of ageing, and the pity of mortality.

Indeed, the whole book drips with the menace of mortality; in every story there's a death, or deaths, although not every story has a death as its central event. Still, Poison Plants and hence Revenge, closes on, and thereby emphasises, the idea of mortality, with this account from the narrator, an old woman, of finding the aforementioned dead child in a refrigerator: I opened the doors - and I found someone inside. Legs neatly folded, head buried between the knees, curled ingeniously to fit between the shelves and the egg box. "Excuse me," I said, but my voice seemed to disappear into the dark. It was my body. In this gloomy, cramped box, I had eaten poison plants and died, hidden away from prying eyes. Crouching down at the door, I wept. For my dead self.

It's not obvious, to me, how to interpret this passage, but whatever it means, and whatever its relation to Afternoon at the Bakery, it gives the flavour of Ogawa's style - at least as it reads through the veil of translation. Peering through that veil, it does seem that Ogawa writes of horror, cruelty, desperation, lives gone awry, in short, exact, even forensic sentences, generally unadorned. The effect is often hypnotically, but precisely, threatening. This, from Welcome to the Museum of Torture, is Ogawa on a dead hamster lying between a crumpled hamburger wrapper and a crushed paper cup in a garbage can at a fast-food place: Its fur was speckled brown, and its tiny arms and legs were a beautiful shade of pale pink. The poor thing almost still looked alive. I even imagined I saw its little paws twitching. Its black eyes seemed to be looking at me. I opened the lid the rest of the way, releasing the smell of ketchup and pickles and coffee all mixed together. I was right, the hamster was moving: hundreds of maggots were worming into its soft belly.

All in all, Revenge is a mysteriously wonderful book, as beautiful as the mould of decomposition soon to be spreading across that hamster. I urge you to read it - and then at once to re-read it, to retrace the many delicate threads that link Ogawa's stories and to re-evaluate what you think she might be saying.

The US edition is published by Picador, and it might be available in parts of Asia, but I read the UK edition published by Harvill Secker, http://www.vintage-books.co.uk.

What few of the stories seem to be about, or at least not obviously, is revenge. Granted, some seem to concern marital, or romantic, revenge: in Old Mrs. J a woman apparently kills in revenge for being trapped in a disappointing marriage; in Lab Coats another woman kills because her married lover prevaricates about ditching his wife; in Sewing for the Heart a bag maker kills because, as he sees it, a customer rejects the bag he has crafted for her, to hold her heart, which lies outside her chest, and hence she also rejects him. But some of the stories seem to have little or nothing to do with revenge. Afternoon at the Bakery, the horrifying first story in which a mother fails to assimilate the unassimilable fact that her child has died in an abandoned refrigerator, seems to be about the way lives can be smashed by improbable, but devastating events; the final story, Poison Plants, which wheels back to Afternoon at the Bakery through the "motif", if that is what it is, of a dead child in an abandoned refrigerator being found by an old woman, seems to be about the loss and degradation of ageing, and the pity of mortality.

Indeed, the whole book drips with the menace of mortality; in every story there's a death, or deaths, although not every story has a death as its central event. Still, Poison Plants and hence Revenge, closes on, and thereby emphasises, the idea of mortality, with this account from the narrator, an old woman, of finding the aforementioned dead child in a refrigerator: I opened the doors - and I found someone inside. Legs neatly folded, head buried between the knees, curled ingeniously to fit between the shelves and the egg box. "Excuse me," I said, but my voice seemed to disappear into the dark. It was my body. In this gloomy, cramped box, I had eaten poison plants and died, hidden away from prying eyes. Crouching down at the door, I wept. For my dead self.

It's not obvious, to me, how to interpret this passage, but whatever it means, and whatever its relation to Afternoon at the Bakery, it gives the flavour of Ogawa's style - at least as it reads through the veil of translation. Peering through that veil, it does seem that Ogawa writes of horror, cruelty, desperation, lives gone awry, in short, exact, even forensic sentences, generally unadorned. The effect is often hypnotically, but precisely, threatening. This, from Welcome to the Museum of Torture, is Ogawa on a dead hamster lying between a crumpled hamburger wrapper and a crushed paper cup in a garbage can at a fast-food place: Its fur was speckled brown, and its tiny arms and legs were a beautiful shade of pale pink. The poor thing almost still looked alive. I even imagined I saw its little paws twitching. Its black eyes seemed to be looking at me. I opened the lid the rest of the way, releasing the smell of ketchup and pickles and coffee all mixed together. I was right, the hamster was moving: hundreds of maggots were worming into its soft belly.

All in all, Revenge is a mysteriously wonderful book, as beautiful as the mould of decomposition soon to be spreading across that hamster. I urge you to read it - and then at once to re-read it, to retrace the many delicate threads that link Ogawa's stories and to re-evaluate what you think she might be saying.

The US edition is published by Picador, and it might be available in parts of Asia, but I read the UK edition published by Harvill Secker, http://www.vintage-books.co.uk.

Wednesday, 31 July 2013

500 Words From Dawn Farnham

500 Words From is a series of guest posts from authors. Here, Dawn Farnham talks about The Straits Quartet, her acclaimed series of novels set in nineteenth-century Singapore and Batavia (Jakarta). The four titles together follow the eventful love affair between Charlotte, sister of Singapore’s Head of Police, and Zhen, once the lowliest of Chinese coolies, and a triad member. In each book, Dawn skilfully weaves romance, scandal, and sex into a satisfying novel, without sacrificing historical accuracy; she includes all sorts of arresting period detail such as what to do in a tiger attack, and how, in the 1830s, passionate girls avoided pregnancy.

Dawn was born in England, but grew up in

Perth, Australia, and her links to Asia are strong. She has lived in China,

Hong Kong, Korea and Japan. She now splits her time between Perth, and her

second home, Singapore. It was in Singapore

that she began to write, fascinated by the rich history of the tiny City-State,

where a variety of cultures mingle, and where, in the nineteenth century the Peranakans,

descendants of male Chinese immigrants and their Malay brides, formed a large and influential population.

So, 500 words from Dawn Farnham:

"What

inspired you to write this book?" Ask any author that question and the

responses will be as varied as the books themselves. For myself, it was a photograph. I had recently become a docent, guiding the

old Peranakan Museum in Singapore and learning the surprising details of

Peranakan homes, food, marriage and lifestyle. A door opened onto an entirely

unheard-of universe and I was taken by this hybrid Malay / Chinese culture.

The photograph was half life-sized. It showed a wedding. The bride was dressed in the old costume of China and the groom like a Mandarin with his gown and button hat. A simple wedding photograph, you might think, albeit exotic, but it spoke to me. For the girl was Peranakan and ought to be in a sarong and jacket, and he was most likely a coolie, newly arrived from China’s shores.

She was a daughter, a more precious commodity in Singapore than in China, for through her were cemented important trading connections to other Peranakan families all over Southeast Asia. But in a smallish community there were never enough men to marry each daughter to a Peranakan male. So she was the means, too, to bring into the family new blood, Chinese speakers, young men who understood China and its ways better than the Peranakans themselves. And a vast supply was arriving with every boat from China. It sufficed only to pick the best of the bunch, ones who could read and write and had canny heads on their shoulders.

The

huge difference from China was that this young man would move into the home of

the bride not vice versa. It was up to him to adjust to this new world: different language, different food, different customs.

So

there it was, the story of a young man, Zhen, handsome and ambitious, out to

make his fortune and to land a rich bride. But that was not story enough of

course. It had to be harder. He had to be in love not with the rich bride but

with the most forbidden fruit of the colony of Singapore, a white woman,

Charlotte, sister of the police chief; he had to face the seemingly impossible

task of coming together with her.

That

was the little seed, and all writers know that the seed is everything. From

that seed, I discovered the life and loves of Singapore’s first architect

George Coleman and his mixed-race Javanese / Dutch / Armenian mistress, Takouhi.

I read about the house he built for her and their child, and I was hooked.

I

hadn’t intended to write a quartet. Somehow that grew along the way when

halfway through the first book, The Red Thread, I realised I had more to say and that the

natural ending of that book led to another – The Shallow Seas. Once I realised I was going to write two,

the next step, surprisingly, was not three but four, hence The Hills of

Singapore and The English Concubine.

Hitchcock

famously said “a movie is life with all the boring bits taken out”. Something

like a quartet of books has to be similar. I’m asking the reader to invest time

in my characters and my duty is to make them and the events of their lives as

lively and dramatic and romantic and passionate as I can. Have I

succeeded? Only readers can say.

The Straits Quartet is published by

Monsoon Books: http://www.monsoonbooks.com.sg/

Visit Dawn’s website: http://www.dawnfarnham.com/

Labels:

500 words from

Saturday, 27 July 2013

Nita B Kibble Literary Awards

Australia's

Nita B Kibble Literary Awards aim to encourage women writers to advance

the cause of literature. The Awards recognise women producing “life

writing”. This includes novels, autobiographies, biographies, and any other

writing with a strong personal element. Two awards are made each year, the

Kibble Literary Award and the Dobbie Literary Award. The Kibble Literary Award, currently

valued at A$30,000, recognises the work of an established Australian

woman writer. The Dobbie

Literary Award, currently valued at A$5,000, recognises a first

published work from an Australian woman writer. The winners of this year’s

Kibble and Dobbie Literary Awards have just been announced in Sydney.

The

Kibble went to Annah Faulkner, for The

Beloved, a novel set largely in a country usually ignored in

literature: Papua New Guinea. This was where Faulkner grew up. The Beloved concerns intergenerational

conflict between a mother and her daughter. When Roberta "Bertie"

Lightfoot is struck down with polio she sets her heart on becoming an artist.

Through drawing, she gives form and voice to the reality of the people and the

world around her. While her father is happy to indulge her driving passion, her

mother will not let art get in the way of the very different future she wishes

for her only daughter.

In 1955 the family moves to Port Moresby, Here, in post-colonial Papua New Guinea, Bertie thrives amid the lush colours and the tropical abundance. She rebels against her mother's strict control, and secretly learns the techniques of drawing and painting from her mother's arch rival. But she is not the only one deceiving her family. As secrets come to light, the domestic varnish starts to crack, and jealousy and passion threaten to forever mar the relationship between Bertie and her mother.

Meanwhile, the Dobbie went to Lily Chan for Toyo: A Memoir, in which the author turns her artistic vision onto her own family's history, to provide an interpretation of her grandmother's extraordinary biography. Toyo is set in Japan before and after war, and also in Australia. Chan is well placed to write about both societies: she was born in Kyoto, and raised in Narrogin, in Western Australia; she now lives in Melbourne.

Toyo, Chan’s grandmother, was born into the traditional world of pre-war Osaka, Her father lived in China with his wife. Her unmarried mother, her father’s mistress, ran a café. As she grew up Toyo understood she must protect the secret of her parents’ true relationship, and thus keep herself and her mother in society’s good graces.

Toyo's life in Osaka was thrown into turmoil by World War Two. Through experiencing the changes of the time, through finding love, and through suffering painful loss, she grew into herself and became more aware of where she had come from. Through it all she clung to her parents’ secret.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)