Chinese Rules: Mao’s Dog, Deng’s

Cat and Five Timeless Lessons from the Front Lines in China

By Tim Clissold

This new book, from the author of

the international bestseller Mr China,

explains how to do business in China – and win.

Part adventure story, part

history lesson, part business book, Chinese

Rules chronicles Tim Clissold’s most recent exploits of doing business in China

and explains the secrets behind navigating China’s cultural and political maze.

Tim tells the story of how he

built a carbon credit business in China, found himself caught between the

world’s largest carbon emitter and the world’s richest man, and saved one of

the biggest deals in carbon credits on behalf of a London investment firm.

Backed by The Gates Foundation, he then set up a new company with Mina, his trusted

lead negotiator from the first deal, but of course, not all goes to plan when

you are playing by Chinese rules…

Tim intersperses his own personal

story with business insights and key episodes in China’s long political and

military history to uncover the five rules that anyone can use when doing

business in modern China. Together, these five rules explain how to compete

with China on its own terms. Rich in entertaining anecdotes, surreal scenes of

cultural confusion and myth-busting insights Chinese Rules is a perfect jumping off point for anyone interested

in contemporary China.

I Ching

Translated with an introduction and commentary by John Minford

With our lives changing at dizzying speed, the I Ching, or Book of Change,

is increasingly consulted, in both China and the West, for answers to

fundamental questions about the world and our place in it. The world's oldest extant

book of divination, it dates back 3,000 years to ancient shamanistic practices

involving the ritual preparation of the shoulder bones of oxen, to enable communication

with the other world. A tool for the attainment of a heightened level of

consciousness, it has recently been an influence on such Western cultural icons

as Bob Dylan, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Philip K. Dick and Philip Pullman. Today

millions around the world turn to the I

Ching for insights on spiritual growth, business, medicine, genetics, game

theory, strategic thinking, and leadership.

This new translation, by distinguished scholar and translator John

Minford, is the result of over a decade of sustained work and a lifetime of

immersion in Chinese thought. Through his introduction and commentary, Minford

explores many dimensions of the I Ching,

not only capturing the majesty and mystery of this legendary work, but also

giving us various ways to approach it and make it our own. With its origins in prophecy and divination,

the I Ching is a system of belief,

refined over thousands of years. In both East and West, more and more people

are now reaching for it to find some stability in our times of uncertainty and

rapid change. Informed by the latest archaeological discoveries, this translation

offers the reader a potent encounter with an ancient way of seeing and

experiencing the world, and an illuminating trip on the path to self-knowledge.

John

Minford has translated numerous works from Chinese, including The Art of War, Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, and

the last two volumes of Cao Xueqin’s eighteenth-century novel The Story of the Stone. He has taught in

China, Hong Kong, New Zealand, and Australia. He is a professor of Chinese at

the Australian National University in Canberra, Australia.

Published

by Viking, in hardback priced in local currencies.

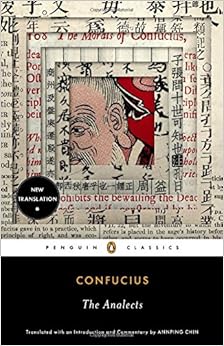

Also of note: the October publication, by Penguin, of The Analects of Confucius in an all-new translation by Yale historian Annping Chin. Paperback, priced in local currencies.